RALEIGH – Perhaps because it has a constitutional mandate for it, North Carolina is known across the country for strong support of its public universities. The state continues to rank among the best in state spending per university student.

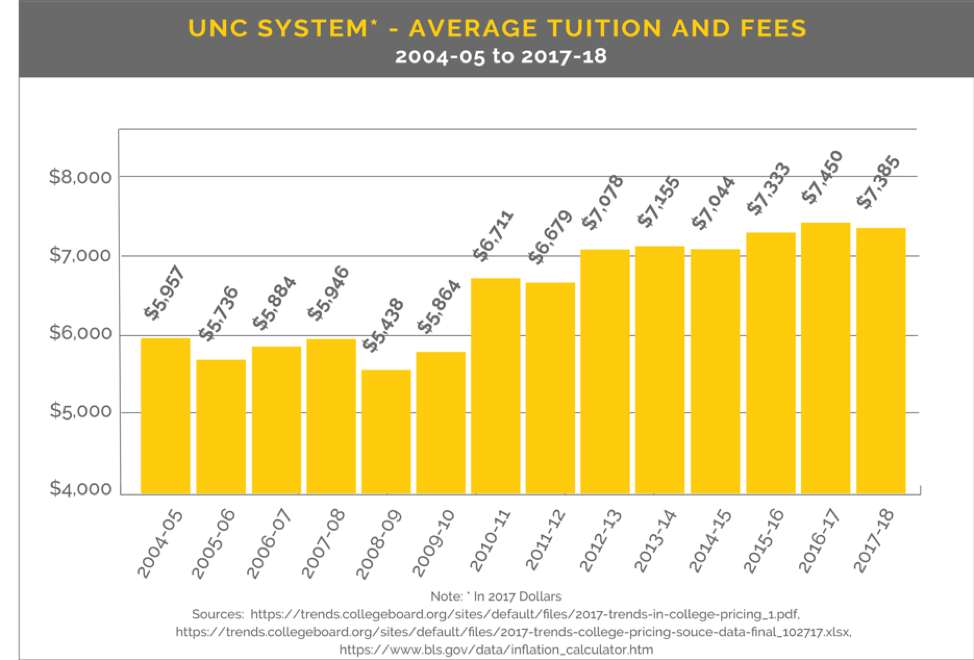

But state support per student is still well below where it was before the Great Recession. And what doesn’t come from the state increasingly comes from increased tuition and fees. Despite its tradition of support, the state has shifted the burden of paying for an education more and more to students and their families.

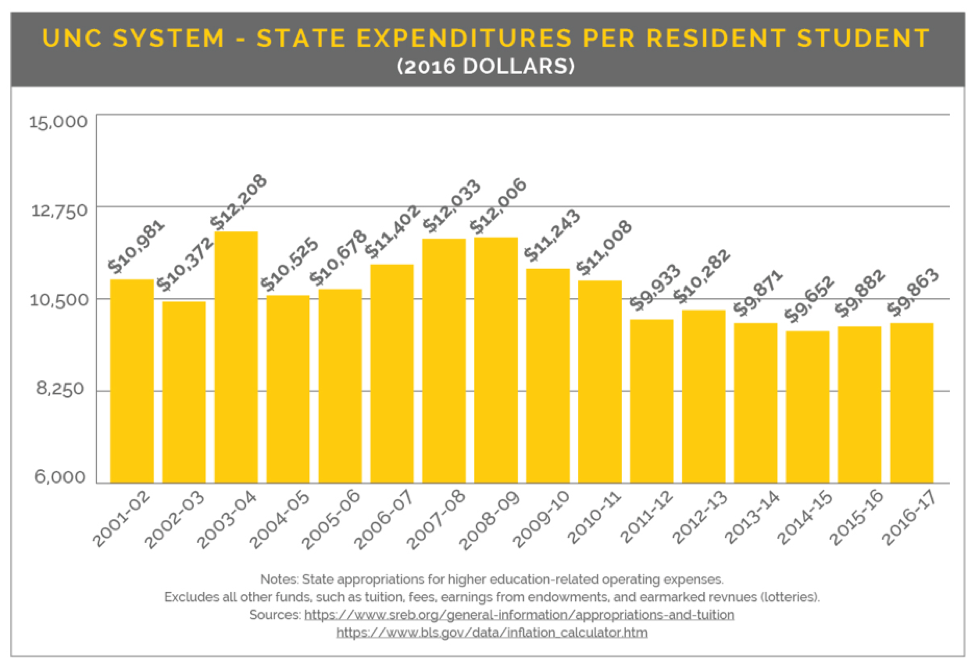

State spending per student in the University of North Carolina System peaked in 2003-04 at $12,208 (in constant 2017 dollars). With the recession in 2008, it began a steady slide until it reached $9,652 per student in 2014-15. It has since climbed to $9,863 – a slight improvement, but still well short of pre-recession levels.

With repeated reductions in state support, institutions began increasing tuition and fees: Where average tuition and fees of $2,641 accounted for just 24.6% of combined state support and tuition in 2001-02, it reached an average of $7,996 and 44.8% by 2016-17.1

The heart of any university is its faculty – the folks who teach our kids. But average faculty salaries in the UNC System have slid for 10 years. And some institutions increasingly resort to hiring part-time, non-tenure track instructors.

UNC System institutions used to aim to rank among the top 25% among their peer institutions in comparisons of faculty salaries.

But that isn’t the case anymore. A survey conducted by the UNC System in 2015 found that average faculty salaries at 11 of the state’s 16 universities fell below the median paid by their peer institutions.2

The System’s two flagships – UNC Chapel Hill and NC State University – would require raises of roughly 6% just to reach the midpoint among their peers.

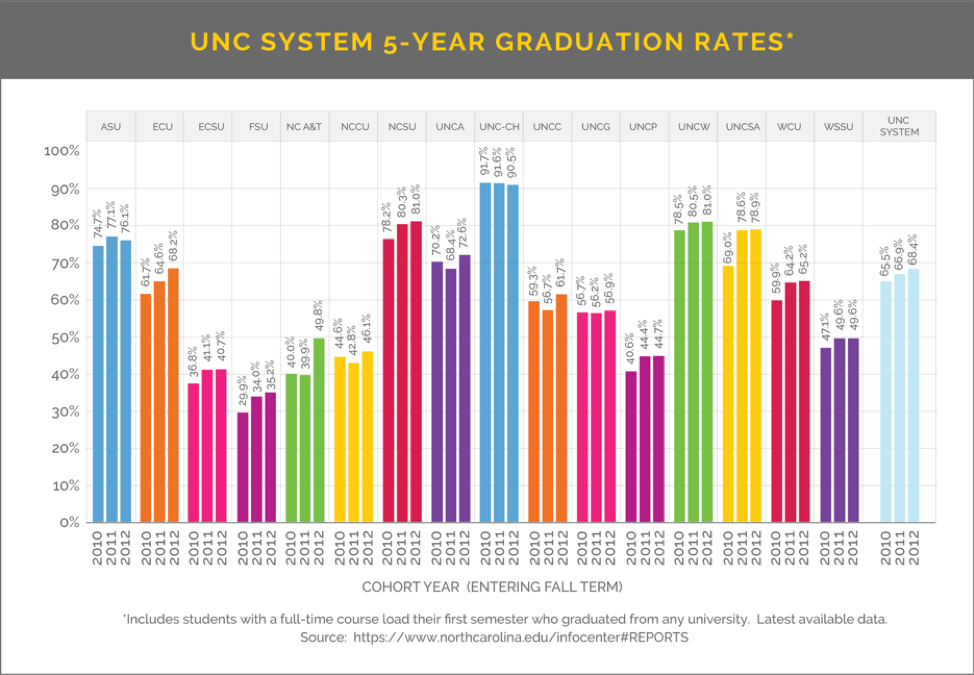

Graduation rates across the UNC System are gradually improving. UNC President Margaret Spellings has placed an increased emphasis on not just getting to college, but getting a degree.

Some institutions have student populations that face more obstacles than others; they have more first-generation, rural or minority students. Because of their proximity to our state’s military bases, some have more military students who are subject to transfers with little notice.

But that doesn’t make their work less meaningful – quite the contrary.

As Spellings likes to say, “Anyone can graduate a class full of valedictorians.”

Yes, we have strong public universities in North Carolina with state support that’s the envy of many states. But at a time when two-thirds of the state’s jobs are projected to require education beyond high school by 2020,3 these investments are vitally important.

As North Carolina’s population has continued to surge, making it the 9th most-populous state in the nation, enrollment in the UNC System has climbed from 185,615 students in 2008 to 209,184 in 2017.4

Those 209,000 students depend on the University to enhance their future, and the state in turn will depend on those students to enhance its future.

If it wants to compete, rather than aim to be average, North Carolina needs to continue to invest in both the University and its students.

1 https://www.sreb.org/general-information/appropriations-and-tuition.

2 http://www.higheredworks.org/2016/03/human-capital/.

3 https://cew.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Recovery2020.SR_.Web_.pdf, p. 3.

Garden C Freeman says

Your comment that our faculty salaries, ET all, is lacking at NCSU may be true, however if the schools don’t start taking better care of their infrastructure then the Prof.’s will not have a place to teach nor will the buildings be safe to inhabit. A million dollars spent on faculty may last 10 years, but a million dollars spent on infrastructure should last a hundred!!! jus sayin!